Tangrams for kids: A learning tool for building STEM skills

Like building blocks, tangrams can teach kids about spatial relationships. They may help kids learn geometric terms, and develop stronger problem solving abilities. They might even help children perform better on tests of basic arithmetic. But what is a tangram?

Invented in China approximately 200 years ago, a tangram is a two-dimensional re-arrangement puzzle created by cutting a square into seven pieces — seven geometric shapes called “tans” (Slocum et al 2003).

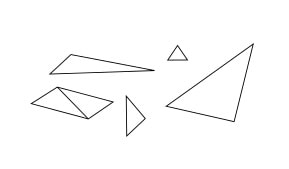

What are the seven shapes in a tangram? Each tangram puzzle contains the following:

- 2 large right triangles

- 1 medium-sized right triangle

- 2 small right triangles

- 1 small square

- 1 parallelogram

Arranged correctly, these tangram shapes can be fitted together as a large square, rectangle, or triangle. They can also be arranged in a variety of complex shapes, including fanciful ones.

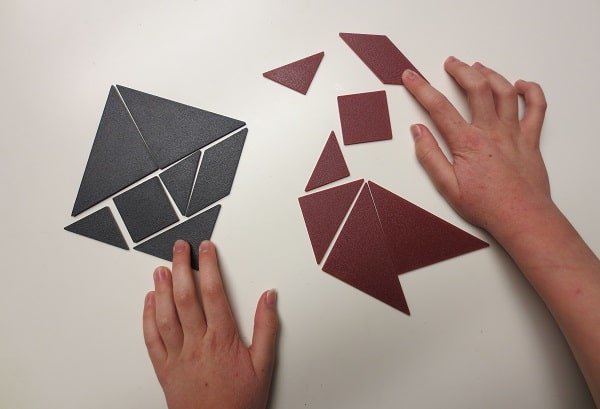

There are many ways to play with tangrams. The simplest way is to let kids create their own complex shapes. But traditionally, tangrams are treated as puzzles, where players are challenged to reproduce specific designs. And there are rules.

The classic rules

The classic rules are pretty simple. To count as a standard solution, players must meet the following criteria:

- a completed design must use all of the tangram pieces;

- every piece must touch at least one other piece, even if it’s just the apex of a corner contacting another piece; and

- all of the pieces must lie flat, with none overlapping each other.

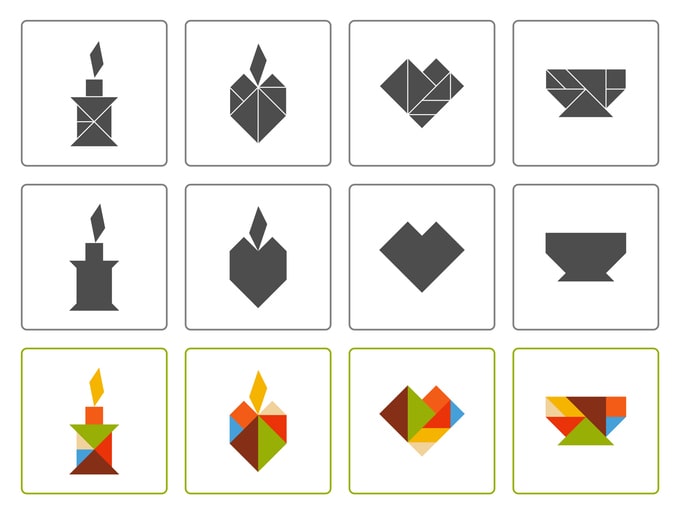

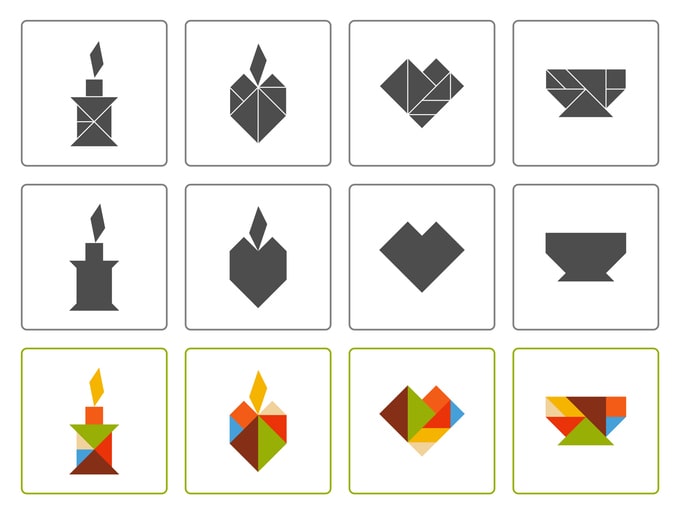

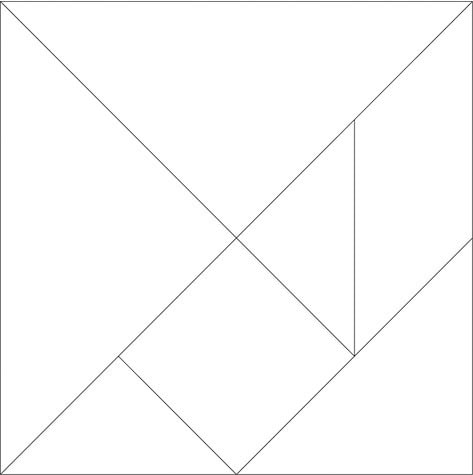

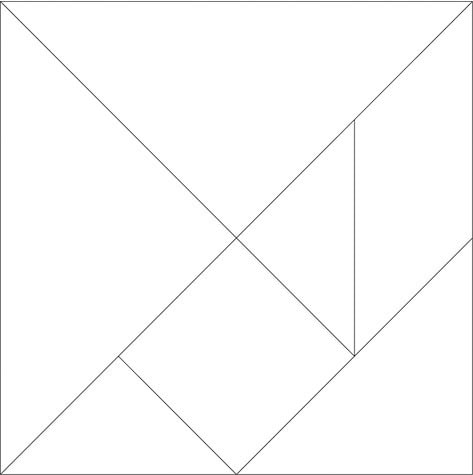

Also, in the standard, classic approach to the puzzle, the player is shown a target shape in outline only, so that the “seams” between the composite tans are concealed. Then the player attempts to recreate the shape using the seven pieces.

In essence, it’s an exercise similar to structured block play, where the challenge is to create an exact copy of a structure depicted in a diagram. But there’s a key difference.

In structured block play, the diagram provides you with explicit, visual information about where each piece goes. With a tangram puzzle, you’re left to figure that our for yourself.

As noted by Zhen Yuan and his colleagues, solving tangram puzzles appears to activate parts of the brain associated with creative thinking and trial-and-error problem-solving (Hu et al 2019).

What makes tangrams especially challenging?

The most difficult puzzles are called classic, “silhouette puzzles,” where players can’t see the internal lines defining the tans that make up a solution. In the image below, the middle row of tangrams are silhouette puzzles. The other rows provide players with explicit cues about the internal structure of each puzzle.

We can make things easier for players by providing them with lines or color cues as illustrated above. But even then, beginners — especially young children — may have difficulty matching the template. Puzzles often require the player to orient shapes in non-standard ways. You may need to turn or flip a piece to make it fit.

It’s not unusual for children to visualize certain shapes with a very particular orientation in mind. For example, students may think of a square not simply as a figure with four equal sides, but as a figure that “sits” flat along the horizontal plane (see image below). If the square is tilted from this orientation, kids might not interpret it as a square anymore. Now it’s a diamond (Clements and Sarama 2014).

This means that players may be slow to recognize the tan they need, even if the shape is right in front of them. If it’s not already oriented in a way that parallels the target orientation, they might not make the mental connection.

No wonder, then, that learning to turn and flip shapes is often a major breakthrough for players. It helps them reinterpret how pieces can fit together (Bofferding and Aqazade 2023).

What are the educational benefits of tangrams?

When we play with tans, we consider the shapes from a variety of angles and perspectives. How would the shapes look if we stuck them together? Rotated them? Slide them around into different positions?

Experiments suggest that thinking about such things — visualizing the spatial relationships between shapes in your “mind’s eye” — can boost our visual-spatial skills.

Research hints that it can boost arithmetic performance, too. When Yi Ling Cheng and Kelly Mix asked kids, aged 6-8, to perform a series of tangram-like spatial tasks, the practice session seemed to prime the brain for mathematics.

Kids who spent 40 minutes solving shape rotation puzzles performed better on a pencil-and-paper arithmetic test immediately thereafter. Compared to tangram-like activities, crossword puzzle warm-ups had no such effect (Cheng and Mix 2012).

So there is reason to suspect that playing with tangrams has educational benefits, and many educators recommended their use in the classroom (Bohning and Althouse 1997; Krieger 1991; National Council of Teacher’s Mathematics 2003; Clements and Sarama 2014).

In particular, these teachers argue that playing with tangrams may help kids

- classify shapes

- develop positive feelings about geometry

- gain a stronger grasp of spatial relationships

- develop an understanding of how geometric shapes can be decomposed

- hone spatial rotation skills

- acquire a precise vocabulary for manipulating shapes (e.g., “flip,” “rotate”)

- learn the meaning of congruence

In addition, researchers have argued that tangram play can be an opportunity for kids move away from simplistic (and incorrect) ideas about shapes. Young children, for example, might struggle to explain what features are necessary for a shape to be a square. With guided questioning, a teacher can help kids determine why some attempts to make a square with tangrams are unsuccessful (Nic Mhuirí and Kelly 2021).

Children can also learn new vocabulary to describe the shapes they assemble (e.g., rhombus, trapezoid, hexagon). And Tom Scovo demonstrates how tangrams can help kids calculate areas without formulas. For the details, see his excellent activities using tangrams for kids in grades 4-6.

What about free play with tangrams? That’s good, too. But take note: Kids probably stand to learn much more if their play includes discussion and teamwork.

Indeed, studies indicate that spatial play — like playing with tangrams — is particularly educational when kids interact with others who use spatial vocabulary.

For example, toddlers tend to develop bigger spatial vocabularies if, during play, their parents expose them to a greater range of spatial words, like “triangle” and “line.” As I explain elsewhere, such kids are also more likely to develop stronger spatial skills.

So it’s likely we can boost the value of tangrams by actively engaging kids in conversation. We can introduce them to words they might not know, like “angle” and “parallelogram.”

It’s also likely that kids will benefit from being asked to make predictions and explain tactics.

Research suggests that kids are more likely to master concepts when they explain them to others. What will happen if you rotate the triangle? What will happen if you flip the parallelogram? How must we move this shape in order to make it fit?

If we can get children to explain their ideas, we may help them improve their spatial skills and comprehension of geometry (Lee et al 2009; Clements and Sarama 2014).

So while kids may benefit from solitary play with tangrams, some of the best educational experiences may arise from playing with a (talkative) partner.

Any other teaching tips?

Tangrams offer kids an excellent opportunity to test out different geometric manipulations, and become familiar with the properties of the shapes they use.

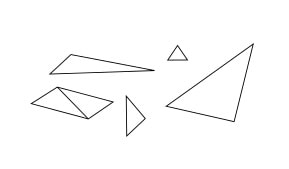

But notice the triangles– big, medium, and small — are all the same shape. They represent a special kind of right triangle — an isosceles triangle with two 45-degree angles, and one 90-degree angle. And if you put together two triangles of the same size, you can make a square.

These properties aren’t found in all triangles. On the contrary! But it’s easy for children to come to that conclusion if they don’t get exposed to a variety of triangles — equilateral, isosceles, and scalene. So it’s important to expose kids to that variety, and call their attention to the ways in which triangles can differ (Clement and Sarama 2014).

Getting started: How to make a tangram

You can make your own tangrams by following the instructions on Tom Scovo’s site, or by printing and cutting out the tangram shapes below.

If you right-click on the image here, you can save it on your computer for printing. Alternatively, after right-clicking, you can open the image in a new tab, and use your browser’s print function.

Looking for more durable tangrams? You can buy some. Classic Tangoes includes two plastic tangram sets and a deck of puzzle cards. But the corners are a bit sharp. You can also find tangrams made from other materials, such as wood, foam, and thick cardboard.

Tangrams for young children

My favorite introduction to tangrams for younger kids is the book Three pigs, one wolf, seven magic shapes by Grace Maccarone. Unfortunately, it’s out of print, but you might be able to pick up a copy used. It includes story (based on the folk tale of the three little pigs), a teaching guide, a set of tangrams to cut out, and some activities created by a math teacher. Although the publisher recommended this book for kids in grades 1-2, the book can be enjoyed by preschoolers.

For another, fanciful story featuring tangrams, see Grandfather Tang’s Story (Dragonfly Books).

Virtual tangrams for kids

You might wonder if computer games are as educational as playing with real, physical tangrams. The National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM) recommends both.

According to the NCTM, computer games may offer special benefits because “the computer environment is likely to encourage [kids] to think about how they need to manipulate the tangram pieces rather than approach the task mainly by trial and error.”

Read more and try out this online game by the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics.

Ideas for tangram activities

The classic approaches are either (1) to present kids with images of target shapes (and have them attempt to reproduce those shapes with their tangrams), or (2) to encourage kids to be creative, and come up with shapes of their own.

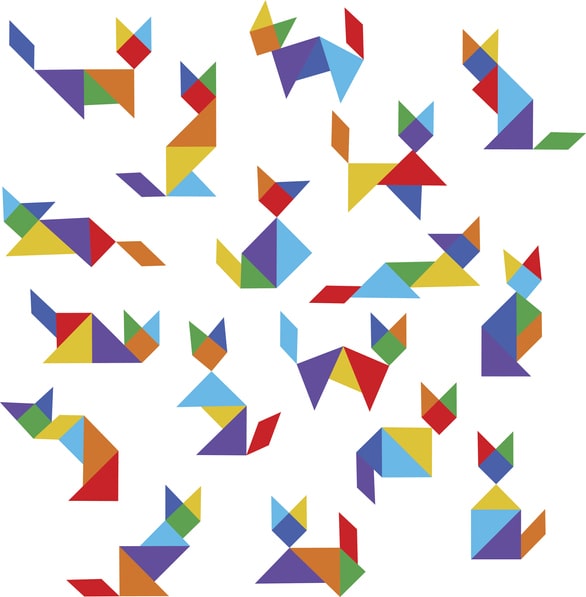

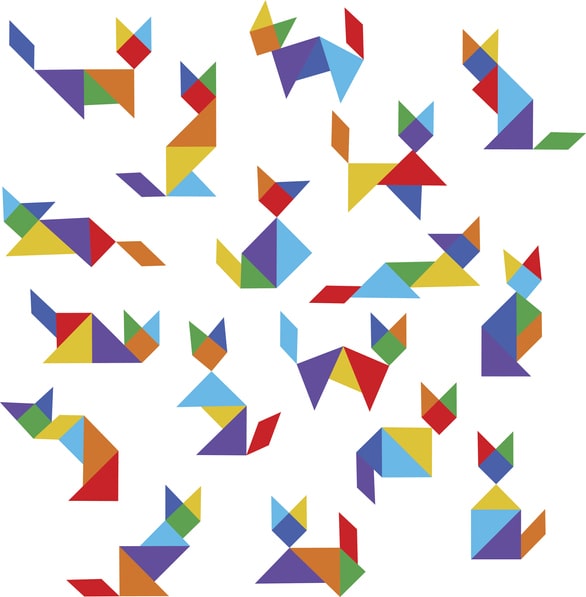

But there are additional games and activities to try as well. You can choose a theme (like “fish” “spaceships” or “houses”) and see how many different examples of each type kids can come up with. For instance, how could challenge kids to create a series of cats.

Read more about learning tactics and the development of STEM skills

For more information about the development of spatial reasoning in children, see these Parenting Science articles:

In addition, to read about the many benefits of construction play, see my article, “The benefits of toy blocks.” If you’re specifically interested in structured block play, check out my article, “Can Lego bricks and other construction toys boost your child’s STEM skills?”

Interested in teaching tactics that help kids learn and retain new concepts and STEM skills? My article about spaced learning reviews the evidence that students are more likely to retain new information if we spread lessons out over time. Elsewhere, I also discuss how we can harness the power of self-explanation to help kids learn math and science. And in this article I recommend a number of STEM books and learning resources for kids, including some free ones.

References: Tangrams for kids

Bofferding L and Aqazade M. 2023. “Where does the square go?”: reinterpreting shapes when solving a tangram puzzle. Educ Stud Math 112: 25–47.

Bohning G and Althouse JK. 1997. Using tangrams to teach geometry to young children. Early childhood education journal. 24(4): 239-242.

Cheng Y-L and Mix KS. 2012. Spatial training improves children’s mathematics ability. Journal of Cognition and Development. Published online DOI:10.1080/15248372.2012.725186.

Clements D and Sarama J. 2014. Learning and teaching early math: The learning trajectories approach. New York, NY: Routledge.

Hu Z, Lam KF, Yuan Z. 2019. Effective Connectivity of the Fronto-Parietal Network during the Tangram Task in a Natural Environment. Neuroscience. 422:202-211.

Kriegler S. 1991. The Tangram: It’s More than an Ancient Puzzle. Arithmetic Teacher 38(9) 38-43.

Lee J, Lee JO, and Collins C. 2009. Enhancing children’s spatial sense using tangrams. Childhood Education 86(2):92-94.

National Council of Teacher’s Mathematics. 2003. Developing geometry understandings and spatial skills through puzzlelike problems with tangrams: Tangram challenges. www.nctm.org.

Nic Mhuirí S and Kelly D. 2021. Making squares: children’s responses to a tangram task. In: Eighth Conference on Research in Mathematics Education in Ireland (MEI 8), 15-16 Oct 2021, Dublin, Ireland (Online).

Slocum J, Botermans J, Gebhardt D, Ma M, Ma X, Raizer H, Sonnevald D, and Van Splunteren C. 2003. Tangrams: The world’s first puzzle craze. Sterling: New York.

Title image of child’s hand’s manipulating tangrams by Gwen Dewar

Line drawings of triangles and tangrams by Parenting Science

Image of many different tangram cats by Sveta_Aho / istock

Content of “Tangrams for kids” last modified 10/2024. Portions of the text derive from earlier versions of the article, written by the same author.